Last updated on 2019.07.22

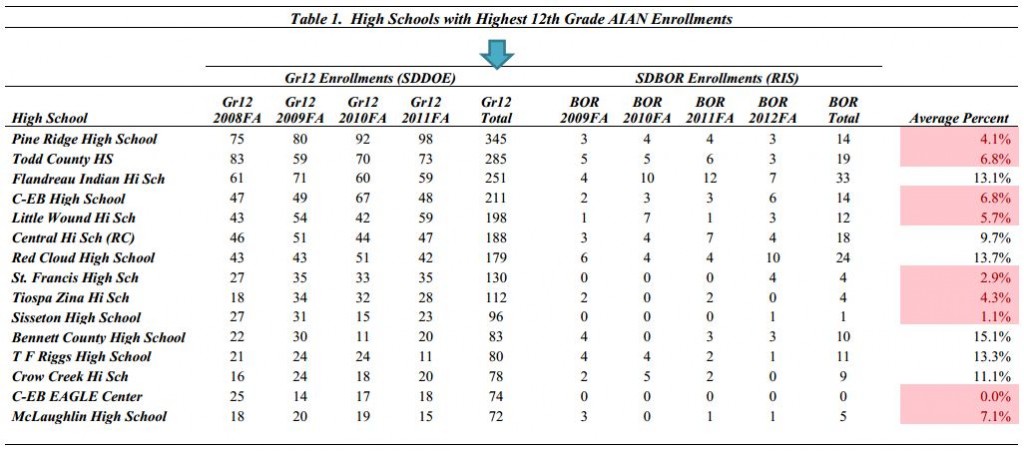

Want to know why South Dakota needs to do more to help American Indian students get into our public universities? Consider this table (click to enlarge) on the percentages of Native students from the high schools with the most Native graduates who enroll in Board of Regents institutions:

Education at South Dakota's public universities may not be for everyone, but it is probably for more than 4.1% of Indian graduates from Pine Ridge, or 1.1% of Indian graduates from Sisseton.

Last week I discussed the South Dakota Board of Regents' report on placement outcomes for their graduates. Noticing that American Indians make up 8.9% of South Dakota's population but only 2.2% of our public university graduates, I suggested that any major initiative by the Regents to meet South Dakota's workforce needs should start with an effort to recruit more Indian students.

A couple of eager readers pointed out that the Regents are a step ahead of me. At their December meeting, the Regents also received "Like Two Different Worlds," a study of American Indian perspectives on higher education in South Dakota. 49 American Indian students from NSU, BHSU, SDSU, and USD participated in focus groups to discuss what keeps Indians from coming to university, what challenges they face at university, and what helps the smart, persistent, and lucky few push through to graduation. The study includes recommendations for Regental action to bring more Indians into higher education.

One obvious problem is money. The crushing poverty of the reservation makes higher education unaffordable for many Indian families. Increasing tuition and cuts to scholarships don't help, but even with financial support, many Indian students find it hard to leave home when their families need every dollar and every worker to feed the kids. Even if they get tuition assistance, many Indian students face campus life in dire financial straits. They can't count on any financial help from home the way many white students can. Having grown up in poverty, Indian students often lack basic personal budgeting skills that the Anglo culture takes for granted. That lack of money and money skills isolates Indian students (it's tough to be part of the gang when can't just head to Dough Trader for pizza on a lark), stresses them out, and drives many students out of school.

A deeper cultural problem is what I might call the tension of the tiospaye. The Lakota/Dakota sense of extended family creates a healthy sense of identity and community. The commitment to the tiospaye holds Indian tribes together in the midst of hardship. It motivates many students involved in the study to go to university and get their degrees so they can better support their families, serve their tribes, and set an example for their fellow Indians.

But the ties of the tiospaye also pull young Indians away from university. As mentioned above, young Indians feel an obligation to stay home and work for their families. Leaving for university feels like abandoning the family. The obligation and guilt Indian students feel is reinforced every time they visit home... and as one student in the study points out, those visits often take place in grim, powerful circumstances:

…if someone’s aunt dies or someone’s mom dies or someone’s brother dies – I mean, the reservation, it’s not an easy place to live. There’s a lot of death on the reservations. And you know when someone dies you obviously you go back to their funeral…and when you go back then you’re going to be like talking to those people again. And then you’re going to realize you miss them. And they are going to miss you, and like you said you depend on them, they depend on you…I think that’s why a lot of Native Americans don’t stay in college, is because they don’t necessarily feel that support or because they feel like they’re needed at home to support those other people. I just think that there’s a lot of like – to me, an image of hands like grasping at people and like pulling them back [student, "Like Two Different Worlds," South Dakota Board of Regents, May 2013].

Remember: our current Congresswoman left college in 1994 when her father died, and we don't begrudge her that choice. Indian students face grim choices like that in their extended families on the reservation more frequently.

The hands of the tiospaye, "grasping at people and... pulling them back," can also push Indian students away. Many students in the focus groups reported that going to university earns them resentment and alienation from family and friends back home. Rather than winning respect, their decision to go to university earns them reactions like these:

"...You're not better than us... You stay here. This is what we've all done."

...some of our friends refused to talk to me....

"...oh, just because you got an education, doesn't mean s---" [students, BOR, May 2013]

One student likens that resentment to the old-time anger at the "hang-around-the-fort" Indians. Another notes that the whole Western notion of higher education and credentialing doesn't fit with Lakota culture. Even our noble universities are imperialist institutions, and Indian students attending them will face accusations of surrender to the Wasicu.

That rejection painfully isolates students coming from the tiospaye. That close-knit community is all that they are. They go off to university and find themselves outsiders in the white-man's world of Spearfish or Brookings. But they come home to find their own families accusing them of belonging more to that white-man's world. To feel like an outsider everywhere and at home nowhere is too great a burden for many young people to take.

The Board of Regents will not single-handedly solve any deep cultural tensions. But the Regents did approve acting on the following recommendations to be acted on immediately:

- Creating a central office position for an American Indian liaison to high schools, American Indian students, and their families. This outreach would go beyond the usual one-time high school visits from admissions office reps. This outreach would include much more follow-up, meetings with students and families explaining the basics of university life, and helping American Indian students fill out their applications.

- Coordinating system-wide efforts to keep Indian students in university. The specific programs the Regents want to use and expand are scholarships, emergency campus funds, special Native orientation programs, summer bridge programs, and (one of the best suggestions) work-study jobs that will send American Indian students out as recruiters.

- System-wide professional development activities for American Indian student service specialists.

- Reviews of mission statements, inclusive language, and zero-racism-tolerance policies.

The Regents also approved three longer-term actions:

- Developing an advisory committee of high school principals and/or guidance counselors to help the Regents develop better American Indian outreach programs and to share among high schools practices that help get more Indian students ready for college.

- Studying American Indian recruitment and retention more closely.

- Strengthening relations between the Regents and South Dakota's tribes... which is the vaguest statement among the recommendations. I wonder... shall we require that one Regent be a tribal member?

If we hear any opposition to efforts by the Regents to recruit, enroll, and graduate more American Indian students, it will likely couched in opposition to "affirmative action" and special favors for certain groups. But restoring scholarships, helping Indian students fill out their apps and FAFSAs, and offering support networks on campus aren't special favors. They are efforts to give our American Indian citizens the same support that students from the dominant culture already get from other sources.

The Regents are headed in the right direction on outreach to American Indian students. The Legislature and the Governor should support them with the resources necessary to bring up those enrollment percentages from Pine Ridge, Sisseton, and other South Dakota communities.

Just as AIs should distrust the state they should be wary of the BOR's Trojan Horse Hockey. NDNs should boycott state institutions and seek higher education elsewhere.

That's a very good post Cory. I taught school in 1981-82 at Crow Creek, the Chieftains. I was blown away by the number of smart, skilled, athletic, creative students there. I'd been teaching at small town SD public schools before and there were lots of good kids there who gave me many, many good memories. They couldn't hold a candle to those students at Crow Creek. Wow.

The barriers truly are immense for those students. One of the phrases I heard scornfully said from one student to another was, "You're an apple." I hear it among young people of other races who say, "You just trying to be white."

So many barriers and so hard. I applaud the Regents work and wonder if 3-4 full time mentors per campus might be a wonderful help. There are enough out there.

Cory, you have truly out done yourself with this post, you have shown understanding and empathy for what these young people go through. Since most young Natives are not full flood, they do struggle with two cultures, for most people it is difficult to tolerate one.

At the risk of someone calling this an excuse, the only thing I would add is the consideration of inter-generational trauma. This is a proven theory that generations of Natives have gone through.

Our youngsters feel the pain of the elders when we talk about the treatment at Indian Boarding Schools, they feel the anguish of not having been old enough to participate in Wounded Knee '73, they feel the hurt when the elders tell them of racism as the result of Jim Crow laws.

I always carried my own resentment because of when my mother was born she was not a U.S. citizen and later could not vote and was also relegated to a second class citizen because of how women were treated in that era.

The white culture(s) have been able to assume or take for granted so many rights guaranteed by The Constitution, while Natives have had to struggle and fight against tremendous odds to have those same rights.

As the anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre approaches many of the elders feel the fear of our ancestors on that inglorious day.

Remembering those stories are in Native Americans DNA. don't forget and don't trust, it is how we have survived.

That's so true about the intergenerational trauma. It's true of a wide variety of groupings of people. Jews - thousands of years of terrorization, no place to call their own. I can't imagine what it's like to go from 70CE to 1948 without a place to call home. What kind of trauma does that inflict on a people to drift from country to country, always existing at the whims of governmental leadership?

The Romany people, Gypsies? Women have endured terrible trauma across the globe and over the centuries. American Indians? Any people anywhere who see half the people who look like them die in massacres, war, from disease. . . I find it so overwhelming to even consider.

There has been so much hardship on this blue dot. Sometimes I wonder about the whimsical force that brought me to life as a woman in the U.S.A. How differently would I perceive the world and my place in it if my skin was dark and Haiti was the only place I'd ever known? Or Brazil, the Congo, Tibet, etc?

Rationality tells us that any attempts to decide what we would do were we Nepalese, Latvians, American Indian, Chilean, Syrian, or any other are simply ludicrous. It's apparent than a much wiser and more productive course than judging them, would be trying to believe and understand them.

That resentment toward those who leave their community for college is by no means a reaction on the reservations. In a writing assignments when students were asked to describe their home communities and their relationship to it, the resentful reaction of former schoolmates in the smaller towns toward those who left to go to college was the most common experience. For the college students, there was an element of trauma because they realized their relationship to their community had changed to a sense of alienation.

Missing from the discussion is how many high school graduates from the reservations enter the tribal colleges. When I first came to teach at NSU, we worked in cooperative ventures with those colleges, exchanging areas of expertise and sharing resources. As the turmoil surrounding Wounded Knee II receded into memory, those cooperative efforts also receded from conscious attention. At that time NSU had responsibilities on

Cheyenne River, worked with and through Blue Cloud Abbey, now closed, and kept lines of opportunity open for educational enterprises on the reservation. That all changed as budgets became the first priority.

Thank you, David, for the inside looks at how universities are bound to their foundation donors. Why South Dakota has devoted billions to maintain multiple campuses and to prop up 66 county seats merely means that the state uses nepotism and cronyism to deny affordable medical care to those who can't afford to buy into the bullshit.

The Regents report does express a desire to work with the tribal colleges, not compete with them. The students in the focus groups express some disdain for the tribal colleges, but then these students are a self-selecting group that has already expressed a preference for the Regental system. What is the total enrollment at the tribal colleges? Would they have data like the Regents' data above on the percentage of graduates that they receive from each SD high school?

You know, David, I was struck by parallels between the American Indian experience and small-town South Dakota experience in general. I don't want to minimize the differences—reservation poverty and white privilege make the Native experience unique; the cultural differences complicate policy efforts to help American Indian students in ways that don't affect general policy.

But when I read comments from Indian students about the tension of growing up in a place where everyone knows everything about you, of feeling simultaneously oppressed yet defined by that connection, I couldn't help but think of things you've talked about in your essays on the small-town culture that shapes the students you've taught at Northern. When Indian students talked about the resentment they experienced back home for leaving and changing (and a good university inevitably wreaks changes on students), I thought of the tension all of South Dakota's best and brightest seem to face when they venture out to the world for education and opportunity, then get rebuffed as outsiders when they try to come back and work in South Dakota (Matt Varilek offers the salient political example).

There is still an important cultural difference. One student in the focus groups talked about the different messages she gets in her mixed family. Mom is white; Dad is Native.

"Mom is always encouraging me to go out into the world and find a place away from home that I want to make a home. She doesn’t necessarily want me to return home. Where, my desire is to return home and help my people out. And I definitely know that that comes from my dad’s side, because my dad’s the third generation of tribal leaders. I mean, he wasn’t the tribal leader but he served on tribal council. And he strives every day to help Indian country and agriculture. And I definitely feel that duty to go home and help out where I can among my reservation. Whereas with my mom’s side of the family I don’t necessarily feel that.

"I think that goes back to like the roots of Native Americans and Indians and their culture. It’s really like stuff with community, you know?"

The Euro culture has a stronger urge to uproot and replant; the Native culture has a stronger urge to stay. How does that affect university outreach to students from those cultures?

Rural culture is so fascinating and frustrating. I graduated from Miller High School in 1971 in a class of 101. The majority of my classmates were going on with education. We were expected to go on with our lives wherever they took us, and to be more successful than our parents. Maybe that's a Greatest/Baby Boomer generational thing. That was a pretty optimistic time and success was expected. I suppose that may have changed in the past 40+ years. I think class sizes are down to about 30 now in Miller.

In 1976 I was teaching in a small school in ESD, Brookings area. There were about 100 students in that entire school and maybe 1/4 were going to college, or something. I think size of the school/town makes a difference.

On the other hand, I spent 6 years in Newell. I had a country church northeast of there too. The church was populated with ranchers, and I was pleasantly surprised by the number of college degrees held. But some of the ranchers without degrees, who seemed to have little respect for education, used poor grammar and sounded unintelligent, though that was not the case.

People are so odd.