When the Regents got done purging David Borofsky from their system yesterday, they took up a Drexel University study of South Dakota's labor market. The study, commissioned by the state Workforce Development Council, looks at our population, education attainment, labor force, and job growth.

One key finding is that South Dakota remains a "net exporter of college degree holders"—i.e., brain drain. We pour resources into higher education, and then, more often than not, other states benefit from the value we've added.

It's not like we're overproducing degrees and suffering from a surfeit of degree holders. Our degree holders are leaving for labor markets in which an even higher percentage of their competition hold degrees:

Approximately 24 percent of working-age South Dakota residents currently hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 28 percent of working-age adults in the United States. While these figures are not far off, differences in the rate of growth in bachelor’s degree attainment since 2000 have been more stark, with South Dakota increasing by only 24 percent while the nation increased by 38 percent [South Dakota Board of Regents, summary of Drexel Labor Market Study, planning session agenda item 6, 2014.08.13].

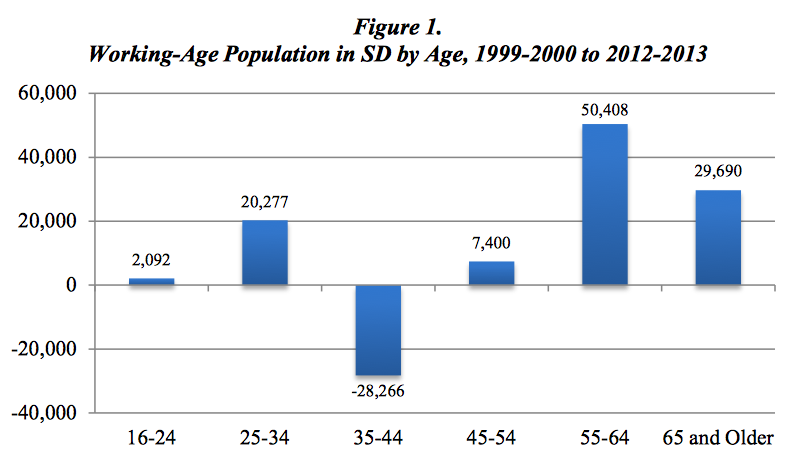

Subtracting those departing degree holders, our working-age population is still growing at about the national rate. Our biggest gains come among workers age 55 and older:

The age groups most likely to have kids in school, from 35 to 54, show a net decline. The major growth comes in the older groups who are probably seeing their kids leave the K-12 schools or the younger workers who aren't yet sending kids to school. Hmm... could that pattern indicate part of the problem South Dakota has rallying the political will to increase funding for K-12 education?

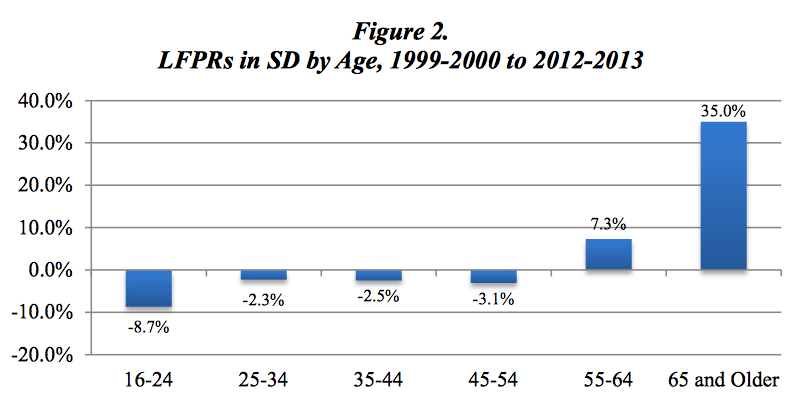

There is a bit of a causal relationship between the higher growth in older workers and slower growth or actual decline in younger workers. As older workers postpone retirement and hold onto jobs, they leave fewer opportunities for younger workers. Consider the stark differences among age groups in workforce participation rates:

Even among those young working-age folks who are staying, we see fewer coming to work, because the big growth in retirement age workers is reducing their opportunities.

The strange thing is that we see those declines in under-55 workforce participation even as a number of South Dakota industry sectors face labor shortages (education is listed, but Drexel cites six others with higher shortage percentages). South Dakota has jobs waiting, but increasing numbers of workers under 55 are dropping out of our state labor force. What's the disconnect? Our fundamental shift from producing goods to producing services is increasing the need for workers with post-secondary training:

The study’s authors observe that many of the labor-scarce industries and occupations identified above are associated with job types that tend to require “long periods of formal schooling, apprenticeships, or other kinds of on-the-job training...to develop the abilities, knowledge, and skills required to work in these occupations,” (p. 48). In other words, the labor shortages currently seen in South Dakota appear to be more characteristic of skilled fields. Conversely, industries and occupations in South Dakota now dealing with excess labor supplies tend to be associated with unskilled positions. These observations speak to the heightened importance of postsecondary training, which the authors found (among South Dakota workers) to be inversely associated with both unemployment rate and duration of unemployment [SDBOR, 2014.08.13].

The Regental response, of course, will be to crank out more degrees. But unless we address our net export of degree holders, that's like pouring more water into the pool but not patching the leaks. We might get better economic results if South Dakota employers did more to retain all the wonderful graduates our universities are already producing by offering them competitive wages.

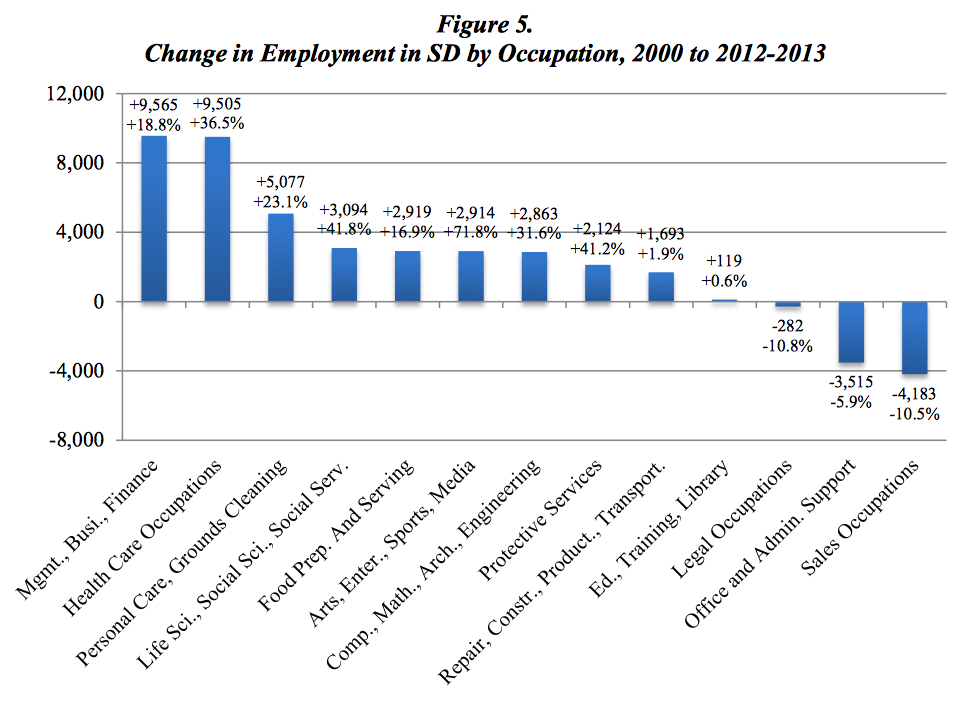

Drexel offers one more interesting the industries that have contributed most to job growth over the last 13 years:

The greatest numbers of new jobs came in management, business, finance, and health care. The highest rate of growth, 71.8%, came in arts, entertainment, sports, and media (an area driven by education in the humanities, not STEM). Notice that Drexel doesn't say anything about job growth in agriculture. Farming is part of the goods-producing sector that Drexel says will diminish in importance because "technological gains outpace the contributions of labor."

In other words, agribusiness and manufacturing can get plenty of machines to do their work. Our universities need to focus on creating more skilled human beings.

Humans. Humanities. Think about it.

While the SDGOP urges people to avoid liberal arts educations to become worker bees: pathetic really.

The decline in the percent of the population employed in agriculture was one of the leading employment stories of the 20th Century, That trend will continue in the 21st Century, bigger, more innovative, more efficient and more expensive machines will continue to be cheaper and more efficient than added labor.

Factors beyond black and white numbers must be considered too. Quality of life. Arts, entertainment, diversity, challenge, openness, transparent government, good environment, and on and on. Well educated people are not often satisfied with an insular, conservative, monoculture.

Moving from an image beyond flyover country takes deliberate, organized effort. SD leadership does very little to change SD culture. Republicans seemy to be happy with the status quo. It's too bad.

Government ag payments should be limited. Big machinery is not quite so important if those on small farms are rewarded and those in huge corporations, etc are not.