Last updated on 2013.01.28

I've met a great many people. My favorites are three Poles, and I love them.... They are all very good dancers—but with Antoni I could dance forever.... Last night when we were dancing I understood him to say, "I would like to samba with you." I asked him to teach me—and he laughed and said, "Teach you—you are doing it now."

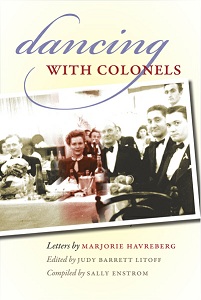

—Marjorie Havreberg, letter to family, Ankara, Turkey, 1944.08.26, from Dancing with Colonels: A Young Woman in Wartime Turkey, edited by Judy Barrett Litoff, compiled by Sally Enstrom. Pierre, SD: South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2011, p. 106.

The South Dakota State Historical Society graced my mailbox with Dancing with Colonels: A Young Woman in Wartime Turkey, a collection of letters home from South Dakota native Marjorie Havreberg. The granddaughter of Norwegian immigrants, Havreberg was born in Carthage in 1914, grew up in Redfield, then saw the world as a government secretary in Depression-era Washington, D.C., and wartime Ankara, Turkey.

To enjoy reading this book, one must be clear about what it offers. Dancing with Colonels does not provide a rich eyewitness account of two of the most dramatic periods of American history. Nor does it provide a tight autobiographical narrative. Dancing with Colonels is a personal scrapbook, providing us glimpses of one woman and the world she saw. These letters are the tantalizing source material for much larger stories to be told, about an America and a woman in transition in a big but shrinking world.

Havreberg was not a historian. In the first set of letters, all from 1936, letters presented here, Havreberg is a 22-year-old South Dakota country girl typing correspondence for Senator Peter Norbeck and experiencing a Washington abuzz with New Deal bustle, then a 30-year-old woman. In the second set of letters, spanning 1944 to 1946, she is a woman tired of Washington and a failed marriage and venturing overseas to work for the American military attaché in neutral Turkey. In neither set of letters does Havreberg record much of the politics or history going on around her.

In Washington, Havreberg gets "a kick out of these poor Congressmen" who "seem to think everyone is one of their constituents" (p. 31). She notes some "uneasiness among her fellow federal employees at the Supreme Court's overturning of the Agriculture Adjustment Act (p. 32). She twice mentions attending "Little Congress," a debating society for Capitol secretarial staff (pp. 5, 32, 50). She writes her mother about her "extravagant" twenty-five-cent daily lunches and a twelve-dollar trip to New York that included a lunch that cost an "exasperating" full dollar—"and then we had to tip" (p. 49).

Havreberg's letters from Turkey show a political restraint that one may expect of a wartime military employee. She shares details of the month-long hopscotch voyage from Washington to Ankara via Miami, Brazil, and Cairo (pp. 95-96). In Ankara, we hear glancingly about the Warsaw uprising when Havreberg mentions that her friend Balo (Antoni Balinski) has not danced with her for two weeks due to the Poles' mourning (p. 122). She refers to the new atomic bombs as "fantastic" (p. 149). She meets a junketing Senator Karl E. Mundt, who "looked well" after a bout with the Pharaoh's curse in Cairo (p. 151).

These details are all snapshots. Dancing with Colonels usefully preserves these snapshots amidst the pages of Havreberg's personal scrapbook. Putting these snapshots in context to tell a fuller story of the Depression and World War II is the work of another author, and another book.

Even though the letters presented in Dancing with Colonels speak much more of Havreberg's personal life than politics, we still get only glimpses of who this woman was and how she felt as she lived through such interesting times. In both packets of letters, we see a small-town girl moving with ease in foreign worlds. As if offering a primer for today's young graduates who might feel a bit nervous about stepping out on their own past the Redfield city limits, Havreberg says her world traveling is no big deal:

...I shall never again be awed by people who have "traveled." Now that I've done it, I know that anyone can & no one should be impressed at all when someone speaks of foreign places familiarly (p. 171).

Scant lines from Washington (p. 53: "haven't time to look back") and Ankara (p. 103 "danced more in the last month—than in the past eight years") hint that Havreberg pursued each adventure in part to escape the restrictions of conventional life and do her own thing. Yet her letters are also shot through with self-deprecatory references to her "selfishness" (pp. 59, 89, 94), suggesting an uneasiness with doing her own thing. We learn not from Havreberg's letters but the editor's Epilogue and a niece's postscript that Havreberg married an old romantic interest from Redfield who "did not enjoy traveling" (Enstrom, p. 186).

Why would a woman who had seen so much marry a man who would not enjoy sharing such adventures? It was as if she felt guilty (p. 59)—

And there is a key line: as if she felt. Havreberg's letters suggest a certain detachment. A letter from Ankara speaks of having "some very good friends":

I like them all so much and hate to know that after these two years I'll probably never see any of them again, but it's nice to know them... (p. 127).

Maybe nice is just Havreberg's Scandinavian restraint, but Havreberg's written language does not capture whatever depth Havreberg's affections may have had. Her social life is a series of dances and dinners and other enjoyable excursions with a variety of interesting people. With men especially, Havreberg's letters capture no arc of changing feelings or relationships. Marjorie loved Balo (or so her younger sister Pat concluded in a late 1945 letter), but few of her words distinguish him from the whirling cast of characters in Ankara. Even two 1946 letters to Balo make only one tentative hint of looking forward: "We'll celebrate our birthdays together next year perhaps" (p. 169). However, within a week, along with a copy of her letter to Balo, Marjorie sends her mother a letter that says, "Life with him—oh well have time to decide" (p. 170).

These very subdued emotional snapshots leave us wondering what happened? The Epilogue tells us Balo met Marjorie when she returned to America in 1946, and he came with her to Redfield to visit her family. Then Balo "faded from the picture" (Litoff, p. 179). Why? Why did he go? Why did Marjorie let him go? Why did she break from the life arc that had taken her to Washington and Ankara? Was it a break, or a natural and satisfying identification of origin and terminus?

I like that this book gets me asking questions. I don't like that this book doesn't answer those questions. Historically and personally, Dancing with Colonels is not narrative. It is evidence for at least two interweaving narratives: a nation taking a leading role on the international stage, and a woman stepping onto that stage, then retreating from it. As with the broader history above, answering the mysteries of Marjorie's choices is the task of another author, and another book.

Thanks for the reading suggestion. I'll look for it. To return the favor here's 2 summer history electives for consideration that are easy to assimilate from the Madville summer cottage.

1. This is the 150th commemoration of the Dakota War of 1862. Over the 1000 were killed, included the abandonment of Neu Ulm, and ended in the US's largest mass execution. Why is it important for SD - because it removed the Dakota people from their lands in central, southern Minnesota, and South Dakota east of the Missouri River (which formerly was in the Minnesota Territory). The Dakota War was the lynch-pin event fostering European settlement into South Dakota, creation of Dakota Territory, etc. The theater of war was the Minnesota River valley. One can use one's French since a major cause of the war was the US breaking the terms of its, Treaty of Traverse des Sioux of 1851. . . . sigh.

http://www.greatermankato.com/documents/DakotaMap2009RevisedVersion.pdf

http://www.exploreminnesota.com/travel-ideas/history-heritage/events-commemorate-150th-anniversary-of-us-dakota-war/index.aspx

http://www.visitgreatermankato.com/Dakotaconflict150.php

And yes, you can grab your favorite historian, put him or her on wheels, and peddle your way through the history lessons: http://www.mywahooadventures.com/uploads/Dakota_War_History_Ride_Flyer_02132012.pdf

2. The second elective is easier, at least the first parts: buy, rent, or use your library card to view the just released, Memorial Day, starring James Cromwell: http://memorialdayfilm.com/. Watch the movie, commentary, and read the writer's brief blog at: http://openthefootlocker.blogspot.com/

This Minnesota written, shot, and largely acted movie is a war movie, but its not a war movie, it's a family movie about the imperative to open the footlocker to share histories and experiences so those who follow don't have to make similar mistakes and foster a better future. The second part of this elective is to put into practice what you've learned at your summer gatherings of family and old friends.

http://www.amazon.com/Memorial-Day-Jonathan-Bennett/dp/B00772M1D8

Enjoy.