Last updated on 2013.06.07

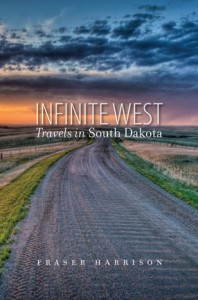

As Americans travel home from summer to fall, my thoughts wander across South Dakota with British journalist Fraser Harrison. The South Dakota Historical Society Press kindly sent me an uncorrected proof of Harrison's Infinite West: Travels in South Dakota to review earlier this summer; the book launches this month.

As Americans travel home from summer to fall, my thoughts wander across South Dakota with British journalist Fraser Harrison. The South Dakota Historical Society Press kindly sent me an uncorrected proof of Harrison's Infinite West: Travels in South Dakota to review earlier this summer; the book launches this month.

In the final chapter of Infinite West, Harrison says his mission is to pay homage to South Dakota by cataloguing and displaying his memories from multiple trips to our state. "Like the small-town museums that I relish," writes Harrison, this book seeks "to preserve something local and personal: the essence of my particular experience in South Dakota."

Harrison presents no compendious travel guide. He mostly ignores the "level and featureless" East River farmland and towns. Of six chapters, only one deals with East River; that opening chapter recounts Harrison's visit to his dying South Dakota namesake, the town of Harrison, six miles west of Corsica in Douglas County. He finds there a "vast emptiness" that seems to fix souls in their homesteads. His visit to Spearfish covers nothing but the antiques store by the Matthews Opera House. His trip up Spearfish Canyon is overshadowed by a dawdling waitress at the Spearfish Canyon Lodge (Businesses! Pay attention! Sloppy customer service can wreck vacations and reviews, not just of your establishment, but of your whole community!).

Nor does Harrison seek a grand unified theory of South Dakota. That's this blogger's game, and Infinite West offers plenty of geographical and historical observations to fuel that game. Two large themes in his western journeys are decay and tension with history.

Harrison seems fascinated by the images of decay and loss he finds in South Dakota. He says he gasps every time he sees the Badlands, that ever-changing landscape of erosion:

...the Badlands... are sculpted by erosion, not built. They are slowly disintegrating, rendering art through collapse and downfall. The Badlands that my family and I first saw in 1992 no longer exists; indeed, the Badlands I saw on the first evening of my present visit no longer existed by the time I woke up the following morning.

...Erosion is an uncomfortable trope for the elderly to brood on. I wondered how the old folk of Harrison would have responded to these crumbling metaphors [Fraser Harrison, Infinite West: Travels in South Dakota, 2012, Chapter 3].

Harrison sees the numerous ghost towns around South Dakota (more than sixty, he says, in Pennington County alone) offering "ghoulish" and "poignant" testimony to our not-so-distant predecessors' failures in our "chief enterprises, farming and mining." Add to that tourism: a visit to the "Original 1880 Town" near Murdo prompts Harrison to recall the similar attraction near Hartford, now closed and collapsing, a ghost of a fake ghost town.

Even the success of Deadwood mingles with loss. Modern Deadwood has built its fortune on gamblers' loss. That success has also contributed to losses in the community: more than forty retail businesses closed after the city adopted large-scale gambling as its raison d'être in 1989. Harrison couldn't find a place to buy a carton of milk. Harrison did find Deadwood's population has declined over the gambling era, from 1,830 in 1990 to 1,272 in 2010. Sometimes we can't win for trying.

For Harrison, Deadwood also reveals South Dakotans' deep tension with history. The city markets itself as a place to "relive those lawless days" of the 1876 gold rush, yet little of that historic lawlessness manifests itself amidst docile crowds of oldsters chunking coins in the fruit machines (that's the giggly British term Harrison uses for slot machines). In Deadwood and beyond, he finds the sanitized history South Dakota sells starts abruptly around the white invasion. South Dakota deals awkwardly and fitfully at best with the details of that invasion, the events prior, and the consequences to the winners and the losers who still live here.

Harrison sees the same historical awkwardness that I saw two weeks ago when Charmaine White Face stood among a crowd in Deadwood and declared all white titles and authority in the occupied Black Hills invalid. He sees the same historical white-washing (you need to read that word twice) that I found in the Deadwood Standard Project's gold mine permit application, which mentions one Jasper flake found in Spearfish Canyon, but otherwise gives the distinct impression that its authors think events of cultural and historical significance in Spearfish Canyon started when our great-grandfathers started digging for there for shiny rocks.

As Harrison tours South Dakota, he finds us imagining ourselves as the virtuous cowboys, adventurers, and homesteaders of Hollywood's Wild West, the same screen mythology that fired Harrison's early fascination with America's West in the 1950s. Murdo's 1880 Town captures this odd fantasy history perfectly. The "Original" 1880 Town originated in the 1970s when locals bought an old movie set and moved it to the current site. There was no town there; it is a Hollywood myth, transported to a convenient I-90 exit.

In response to that historical tension and myth-making, Harrison takes us to Wounded Knee, "the quintessential locus of the Sioux's subjugation." Harrison says everyone should visit the site of the 1890 massacre, the bloody consummation of South Dakota's original sin (i.e., the sin to which South Dakota owes its origin as a state). Harrison tells the history of the massacre in the context of the drought, despair, and dismantling of the Great Sioux Reservation in 1889 and 1890. He notes that the United States celebrated the murder of three hundred-some Lakota men, women, and children by issuing twenty Medals of Honor to its soldiers, more than issued for any other battle in U.S. history, including Normandy and Iwo Jima (and the army still officially calls Wounded Knee a battle, not a massacre or a mistake).

Wounded Knee is a hard place to visit. It is a remote site, with no amenities. The monument and burial ground there are poorly maintained. More importantly Harrison senses that Wounded Knee lacks the "'compenstory' sense of peace" that he finds at other cemeteries and battlefields: "I have never felt it when visiting Wounded Knee, where a spirit of grief and rage seems to hang in the air." Yet we cannot cover this grief with Hollywood mythos; we must confront it by visiting Wounded Knee, says Harrison, to grasp the Native loss on which we built our state and our nation.

South Dakota as land of decay, loss, and historical tension—sounds grim, doesn't it? But don't misread Harrison: this Englishman comes to South Dakota because he loves this place. His is greatly moved by the Badlands, the rivers, the history he finds here. Through his pages (under 200, an easy read), Harrison comes across not as a nag but as an amiable travel companion. As an Englishman enticed here by the same mythos that soothes and, to some extent, defines us, he helps us see around our glossy Travel SD brochures to a more real portrait of the South Dakota that one eager visitor sees and that we locals will do well to understand.

Awesome note. Thanks for posting it here. Two thoughts.

1. It could be wonderful if the tribe, BIA, and NPS were to cooperate on invigorating a Wounded Knee site of the quality and on the order of the Greasy Grass and other sites in which the NPS assists with administering. Gerald Baker and /or his brother could be instrumental in such endeavor, though they likely are very busy in their retirements or near-retirements.

2. Fraser Harrison should consider on his next trip beginning in the former Minnesota Territory - which, in part, became South Dakota east of the Missouri River. The penultimate event shaping South Dakota was the Traverse des Sioux Treaty of 1851, the breaking of it, the Dakota War of 1862, and the fall-out. The fall-out, in part, resulted in 3 reservations in the west of the Minnesota Territory (Sisseton-Wahpeton, Crow Creek, and Flandreau; and ceded Dakota lands east of the Missouri to the 'illegal aliens'. The government, a few years later created Dakota Territory, in part by separating off the western part of the Minnesota Territory.

The modern history of SD is more than floating up the Missouri River, banishing Lakota from the west river prairies; but the over-looked and central aspect is the subjugation of the Dakota that began in south central Minnesota in the mid-1800s.

icymi:

http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2012/10/15/gap-manifest-destiny-t-shirt-sparks-outrage-in-indian-country-140007